This might seem obvious, but choosing the exact bits of bamboo you’ll use for your bike frame is one of the most important things to do in the frame building process. You need to know a lot of stuff before you can choose the right bits thou! Read on for a few pointers I’ve picked up along my bamboo selection journey.

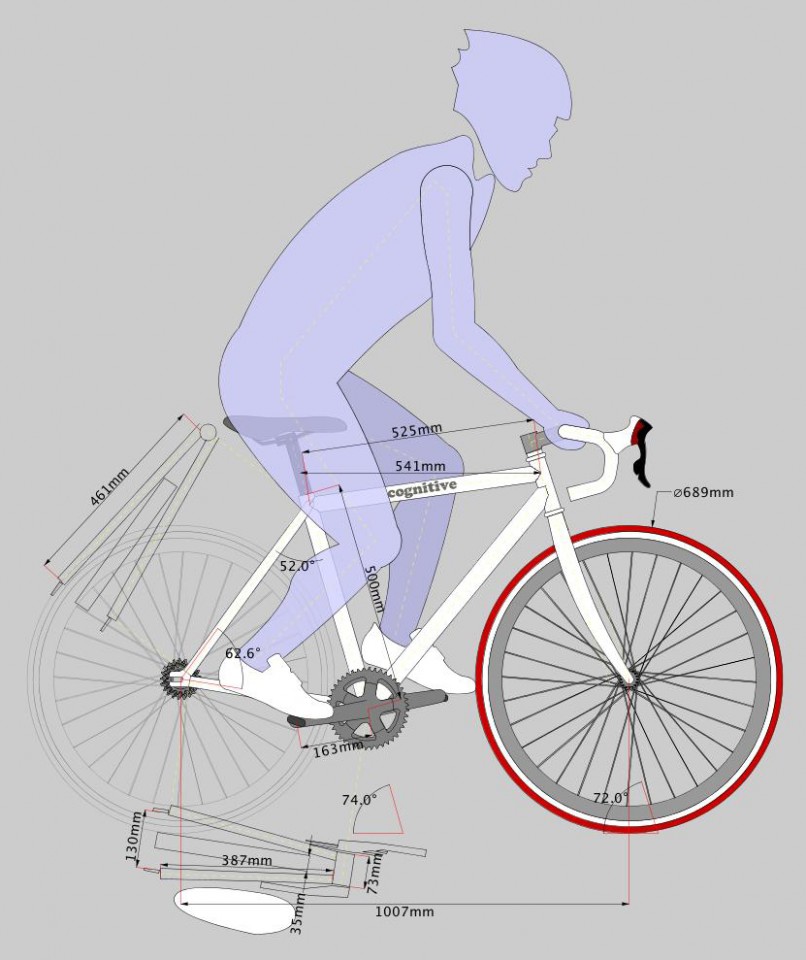

So you’ve got your geometry right and you know what lengths of each bit of bamboo you need. So off to the shop/woods right? Wrong! You’ll need to know what diameters suit which bits of the frame and then work within a set of tolerances that you know won’t cause problems (or be willing to fix those problems in creative ways!).

The rear chain-stays are by far the hardest bits to work with, followed closely by the seat-stays, then seat-post. The top and down tubes are fairly open to how much trust you have in the strength of bamboo. You could go for skinny poles if you want a retro steel looking frame, or fat chunky one that might weigh a bit more, but are probably stronger, like on an aluminium or carbon frame.

The main problem areas (and questions to find answers to) are:

- Tyre clearance – what’s the widest tyre you want to put on your frame?

- Chainring clearance – how many chainrings? How many teeth?

- Crank-arm clearance – what’s the Q-Factor (width) of your cranks?

- Seat-post – what diameter and length will you need? Are you going to use a metal sleeve inserted into the bamboo for the seat-post to go in?

- Disc rotor clearance (if you’re using them) – how big are the rotors?

Only once you’ve got all those questions solved are you then ready to go in search of bamboo with the right diameter!

A rough diameter guide

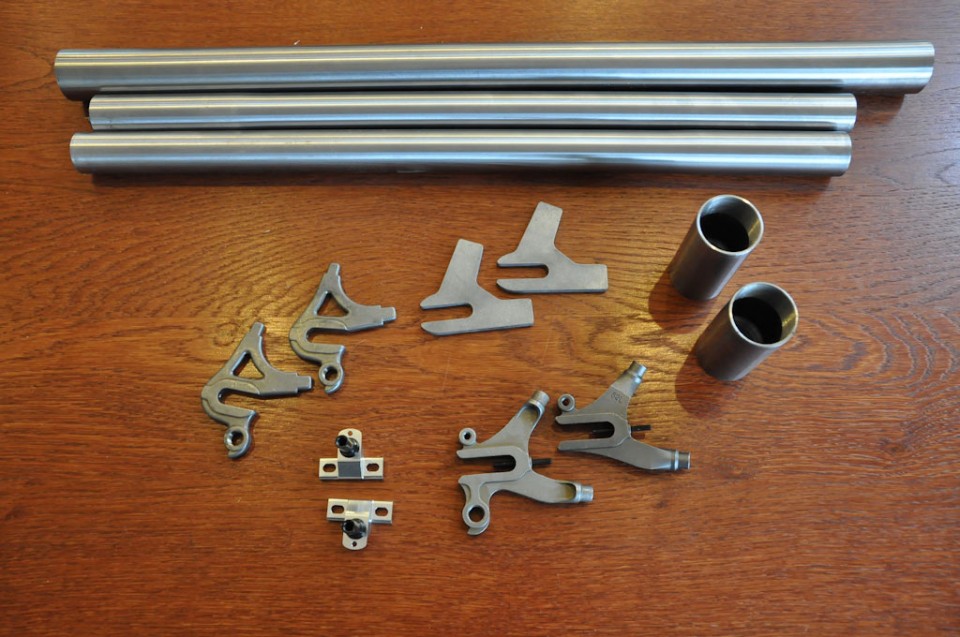

The figures below are a rough guide to what you might need for a road or cyclocross frame. The figures in brackets are what I’ve used on my first frame.

Top tube: 26-36mm (35mm)

Down tube: 35-45mm (41-43mm tapered)

Seat tube: 40mm (the inner diameter needs to be more than the metal sleeve, which if you’re using a 27.2mm seat-post is around 30mm)

Seat stays: 20-25mm* (22mm)

Chain stays: 20-25mm* (25mm)

*Tyre and chainring clearances end up being very precise things, so try to find bits that will exactly match your spec.

What to look for in choosing your bamboo.

So you know what diameters you need. What else is important in your bamboo selection process?

Nodes

I still can’t find out decisively if nodes are strong or weak points in bamboo. Books tell me one thing, the internet tells me others. It’s confusing. If anybody has any definitive information on node strengths & weakness please let me know. What I think is right is that they add strength from crushing forces, but cause weakness from bending forces.

Wall thickness

Bamboo varies wildly in wall thickness from species to species, and due to its tapering nature will often be thick at one end and thin the other. Use the thick ends for areas of your frame you think will be under lots of force I guess. Where are those areas? All over the place!

Straightness

They don’t have to be dead straight, but my feelings tell me that any bends and kinks in bamboo will only make it weaker and more likely to fail when put into the triangle formations of a frame. A triangle with a bent side can easily be crushed!

Roundness

Bamboo is often not round! Lots of the pieces I’ve dealt with are quite oval shaped. This can be a good thing. Oval shapes provide more strength in certain directions. Use them on chain-stays and down tubes to your advantage.

Defects

Wood borers seem to love bamboo and often you’ll find pieces with trails left by these little critters. Most of the time they just eat the surface “skin” of the bamboo and don’t do much structural damage, but this surface is the strongest part or the culm, so if they’ve eaten away large chunks of it, or ring-barked it, be warned!

Cracks, scratches and splinters are also things to look out for. Remember this thing is going to be on a bike for a long time. Find the best bits you can!